The Chantry Riot

- ellieswinhoe

- Oct 8

- 8 min read

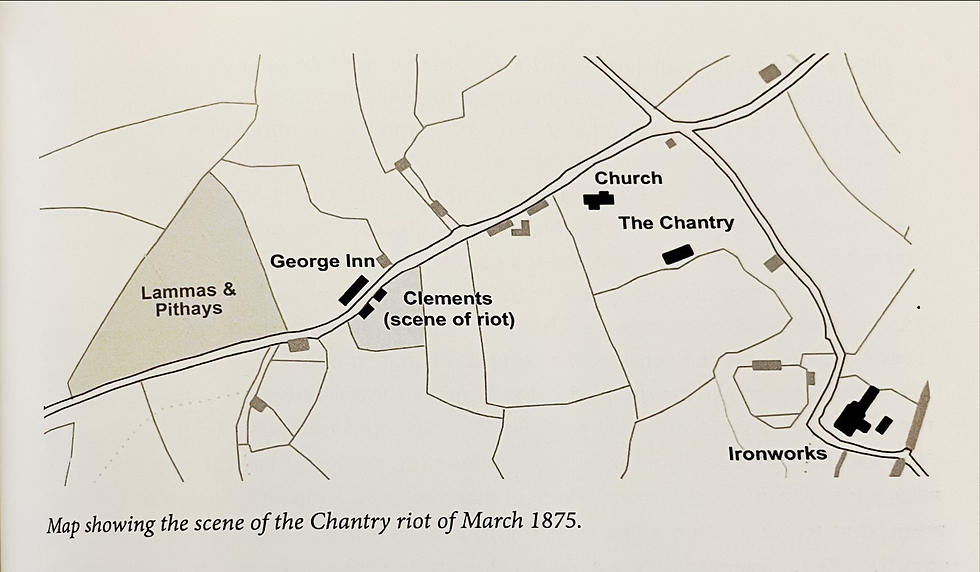

We were lucky to have a visit from author and historian Robin Thornes a couple of weeks ago. Robin is well known to our community and is a former resident of Stoney Lane in Chantry. He gave us a fascinating talk about Chantry - focusing on the formation of the village. He touched on the subject of The Chantry Riot which is included as a chapter in his book Men of Iron, The Fussells of Mells. I thought it would be interesting to feature this chapter here on the blog - it makes great reading - notice how Chantry is referred to as Little Elm at the time of the riot. Enjoy!

From Men of Iron by Robin Thornes - The Chantry Riot

The most bizarre event in the story of the Fussell family must surely be the contemporary descriptions and reports of the legal proceedings that arose from it. On the 31 March 1875 the Frome Times announced: "A serious disturbance took place on Thursday at Little Elm by a large body of colliers, who assisted to obtain for one of their fraternity forcible possession of a cottage and land, the title of which was in dispute."

The property in question comprised a cottage, two fields and a close opposite the George Inn. It had been bought in 1806 by a farmer called Thomas Bryant from Kilmersdon and was the only part of the Stoney Lane estate not sold to James Fussell. The 1851 census described Bryant as a farmer of seven acres, a tiny holding even by the standards of the period. William Michell later described him as the "most quaint and interesting of my people", recalling how he "used to speak of the hard times of his youth, back into the last century, when he was sent into the fields at daybreak, bird scaring 'with a leetle bit o' barleybree-ad as big as my two fingers, an' that was all I had till I comed home for supper'". From these humble beginnings Bryant "got some education, and a little property, land, cows and pigs, on which he and his old wife lived". In fact, he married twice. Sarah, his first wife, died in 1852 and a year later, at the age of 64, he married Mary Ann Wilcox from Leigh-on-Mendip.

Mary died in 1870 and the childless Thomas, an octogenarian living alone, became of considerable interest to his nephews and nieces. He was aware his death might lead to family conflict and yet made no will and only one specific bequest, entrusting its execution to the Reverend William Michell.

When nearing his end, he desired me to take charge of £50 for a niece, which I did, stipulating that there must be no change in his disposal of his money, and had his determination in writing. Very soon this matter leaked out, and attempts were made to alter this disposition. But I had banked the money in my own name, and stuck to his instructions. There was discontent and grumbling, suggestions that he had altered his mind. But the money was paid over by me to his nominee, and I heard no more of the matter. It would have been safer for me to have declined the trust. But the money was in gold, in his house. And if I had not removed it, someone else might have done so.

Following Thomas's death a nephew from Stoke Lane, also called Thomas, claimed his uncle had bequeathed the cottages to him on his deathbed, although the fact that Michell had received no written instructions in the matter casts doubt on this assertion. Other members of the family did not accept the story, arguing the property belonged to them all. In the meantime, another relation seems to have taken it on himself to sell the property to the Reverend James Fussell. Unaware of the transaction, Thomas Bryant took possession of the cottages, only to be told they were the property of James Fussell and that he must vacate them within six months.

Two weeks before the riot, Bryant paid one of his occasional visits to Chantry and found that James Fussell's bailiff, William Gough, together with his coachman had entered the premises and removed his furniture, stopped up many of the windows, put new locks on the doors and moved some of Gough's furniture into one of them. Returning a few days later, the Bryants and some friends forced an entry, only to be ejected by a body of grinders called out from the nearby edge-tool works. Thomas Bryant then openly declared his intention to bring "a body of men to take forcible possession of the premises" at the expiry of the notice to quit. The East Somerset Telegraph reported that "to meet any emergency" James Fussell's grinders had been provided with "substantial truncheons" and thought it likely that "a scrimmage will result".! Thomas Bryant was a coal haulier from Stoke St Michael and his son Francis a coal miner. The Somerset miners had recently become unionised and the Bryants seem to have tapped into this network to drum up support from a number of pits in the coalfield.

On the day of the riot Thomas and Francis appeared in the village at the head of a large crowd of miners, who had converged on Chantry from Leigh-on-Mendip, Mells, Stoke Lane, Coleford, Radstock, Clandown, and Holcombe. The size of the mob was later estimated at between 200 and 300, although among these were hangers-on and local residents who had either come to support Bryant or simply to watch. Sometime after 9am Richard Cox - watchman at the ironworks - and a party of grinders occupied the cottages and made ready to defend them. Sergeant Edmunds later described how "Mr Fussell sent for me and told me he had sixty men on the premises and that they would fight desperately". The "substantial truncheons" the Fussells' men were armed with were wooden staves made at the works - presumably turned on the handle makers' lathes. One of these weapons was later produced in court and was described as "rather shorter and stouter than a policeman's truncheon...a formidable looking bludgeon". Because trouble was expected there was a police presence in the village that morning. PC Abel Chandler arrived at 10am to find a large number of people, men and women, moving towards the cottages "in groups of twelve or twenty". PC Chandler went to the cottages and advised one of the grinders to lock the front door and let them break it, as that would "constitute a damage".

By late morning police reinforcements were on their way to Chantry from Frome under the command of Sergeant Gerrity. On approaching the village at 11.55am, Sgt Gerrity heard a loud cheer and on arrival saw a crowd "in a very excited state". He later described how he witnessed "men with crowbars battering down what appeared to be newly-erected masonry, and smashing out the frame-work and glass of the windows of two cottages". Shortly afterwards, PC John Best saw some of the Fussell grinders pulled out of the cottages "by main force", while William Gough would later testify that he had been standing in the doorway of one of the cottages and had been dragged out and thrown into the garden. Richard Cox corroborated Gough's story, testifying that he saw eight or ten of the attackers pulling Gough out of one of the cottages. Cox also claimed to have seen Stephen Russell of Finger Farm, Mells, incite the mob by calling out to them "go in my lads". One of the coal miners, John Hiscox, then began throwing furniture out of a window until PC Best called on him to stop because he was breaking the law. Hiscox desisted for a while but then resumed at the urging of the crowd outside.

The police constables, being greatly outnumbered, wisely decided not to charge "so large and excited a mob". Instead, Sgt Gerrity went to Mells and returned with the Reverend John Horner, who in his capacity as local magistrate addressed the colliers "in a kind and conciliatory manner, and advised them to go home"? Meanwhile, a telegraph message had been sent asking for reinforcements, but by the time Superintendent Morgan arrived from police headquarters with 20 constables it was evening and the village was quiet. Bryant's supporters expected Fussell to make an attempt to regain possession of the cottages the next day, and so established a chain of "stations" from Chantry to Radstock in order to be able to bring a still larger force of colliers to the village at short notice if the need arose. When no move was made to repossess them, the colliers were stood down and Bryant and a few friends held a party amidst the wreckage to celebrate their victory.

The last act of the drama was played out in Frome Magistrates Court. Thomas and Francis Bryant, along with 20 of their supporters, were summonsed to appear before the petty sessions to answer a charge that "they did with divers other evilly disposed persons to the number of 200 or more unlawfully and riotously assemble to disturb the public peace, and did then and there make a riot and disturbance to the terror and alarm of Her Majesty's subjects".? The prosecution was brought by the Reverend James Fussell - the Frome Bench having declined to advise a prosecution on the part of the police, while the chief constable refused to institute proceedings on the grounds of expense and the fact that a question of title was involved.

The magistrates decided a riot had indeed been committed and proceeded against 11 of the defendants, including Stephen Russell. The case was then adjourned until 11 May. In the intervening period Henry McCarthy, solicitor for the defendants, took out summonses for riot, wilful damage, and forcible possession against the Reverend James Fussell, his son James and a number of their company's employees. It was decided that both cases should be heard together and the court was crowded with spectators hoping for a good show. The outcome was an anticlimax, the magistrates deciding not to proceed with either case on the grounds that a question of title was involved and that it should, therefore, be heard in the Court of Chancery. The Frome Times reported that "considerable disappointment was expressed at the sudden termination of what was expected to be a 'big affair' "

There are a number of aspects to the episode that are hard to explain. The first is that James Fussell must have bought the cottages and land without receiving any clear proof of title from the vendor. The second is that throughout the period in question the Poor Rate books for the parish list Thomas Bryant rather than James Fussell as owner of the property. In the event, James Fussell did not bring a Chancery case to establish his title and Thomas Bryant remained in possession of the property, which later passed to his son Francis. Francis married Jane Toop of Chantry in 1880 and emigrated to the United States, settling in Pennsylvania, where his son Henry was born in 1883. However life in America does not appear to have suited the Bryants, for by 1889 they returned to England and were living in Bedminster, from where they then moved back to Chantry. Today the Bryants' house is called Sunny Nook, a quaint name for a building with such a turbulent history.

Many thanks to Robin Thornes for giving his permission to include this chapter on the blog. "Men of Iron - The Fussells of Mells" is published by Frome Society for Local Study.

Comments